Precedents, part 2 of 3

Dad, Mom, TV, Books, Cousin Palsy and the Kuties

With his checkered childhood and juvenile criminal record, my teenage 1940s Dad was a prototype of what would be called in the 1950s a Greaser, and in the UK, a Teddy Boy. After the January 1949 wedding, Pop asked him what he proposed to do for a job. Dad laughed in his face. Something changed his mind — could have been the kids, though we didn’t come immediately. Eldest brother Tom appeared in February of 1950. But babies = motivation, as I would learn for myself decades later.

In time, he became the man who took every minute of overtime he could grab, worked second jobs, sometimes working around the clock. He did everything he could to provide for us. Yes, and he was crabby from time to time, but who could blame him?

He began at Safeway, checking groceries. Then he swept floors at the Omaha Bakers Supply, (where he would later moon light with his two elder sons in tow, as related in the first installment.)

He would not be there long. Grandmother Bertha also had a job — at the Omaha Flour Mill, boxing up cake mixes on the production line. Grandma got Dad a sweeper job at the mill, and he made something of it. In time, he was noticed by the Head Millwright, who took him under his wing and into the maintenance crew. That crew had a hierarchy; at its peak was the Millwright, a true jack of all trades, reading blueprints, installing and maintaining a wide variety of machinery. So Dad was provided with a goal he would eventually achieve.

When I was 25, while employed as an actor apprentice at the Alley Theatre in Houston, I wrote a song for Nancy Duncan at the Omaha Children’s Theater for her 1976 production of Alice in Wonderland. It was a curtain raiser sung by the playing cards busily slapping red paint on white roses at the behest of their Red Queen. Only later, I realized it was pure autobiography.

My father was a Jack of all Trades

My mother was a diamond in the rough . . .

So in the mid 1950s, when I awoke to the fact that there was such a thing as a job, Pop was reading meters, while Dad and Grandma worked at the Mill. Mom stayed at home, but you would not confuse her day to day routine with leisure. It was an endless round of baby care, food prep, laundry, house work, baby care, food prep, laundry. housework — times six. (When she took a sales job after all of us were launched, a co-worker remarked: You mean you stayed home all those years and stayed thin? Yes. She did.)

Out of the comfortable fog of infancy crept a persistent question: What will I do for a living when my time comes? Based on my parents’ model, I would expect work to be physical, and likely uncomfortable, nothing to do with personal fulfillment.

However, there were other influences on my thinking. Among them were television, reading and music.

The television in our family home was heavily used. Fussing with the rabbit ears, changing channels with pliers when the dial broke off, the picture flipping vertically or dissolving into a blizzard of snow — we did not complain. What would we compare it to? We eagerly absorbed its offerings.

Three modes of employment stories were portrayed: blue collar types, such as The Life of Riley and The Honeymooners (familiar, though the characters were often clueless buffoons;) guys who went to work in their Sunday clothes — Father Knows Best, for example, (difficult to relate to, outside my experience;) and the hyper rich (not relatable at all.)

But all of them were actors, and sometimes they stepped through the fourth wall to identify as such. Especially on variety shows, players would conduct lessons on technique for, say, double-takes, or punchline timing. Jack Benny above all, and others of his ilk, got my attention. On the early talk shows, a young Richard Burton would recite Shakespeare. I was enthralled. Hans Conried played a dazzling array of characters on the Danny Thomas Show, from Lebanese Uncle Tonoose to a down and out, barnstorming classical player, (a life role I would one day undertake.) From my earliest days, I watched all this more like a student than an audience member.

In addition to television, books showed me a world beyond South Omaha. My Grandmother Bertha Lyons had been raised in a household where both beer and poetry were held in the highest esteem by her father, Dave. Reciting out of McGuffey’s Reader was a regular ritual for their family. Though Dave died in 1945, six years before I was born, Grandma continued the tradition with me. Seated, rapt, at her kitchen table I soaked in the poetry and stories with breathless enthusiasm. Leigh Hunt’s Abou Ben Adhem was a favorite, to give an example.

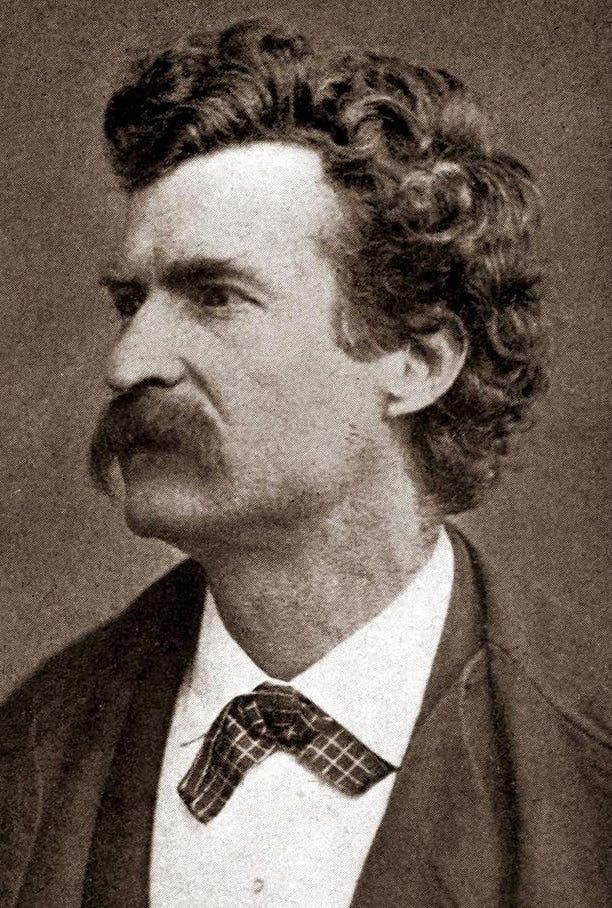

So I was primed and eager for school, eager to read. My parents bought an array of children’s classics, and I buzz-sawed through them all, some more than once — Treasure Island, Black Beauty and others. But it was the Adventures of Tom Sawyer that I read so repeatedly that I was able to recite an entire chapter to my long-suffering classmates in fourth or fifth grade. So Mark Twain rose over my world like a magnificent sun. He has yet to set.

I wanted to BE Mark Twain. Summer trips to the library gave me access to the rest of his works, and it was not long before I was writing myself — vacation journals echoing Innocents Abroad, long stories, doggerel poems. And songs.

Of course there was music on the radio, but my experience was much more immediate. Related somehow on Mom’s side of the family was Cousin Palsy, who fronted a country band featuring at least one of his kids. We saw him at gas station openings. Also, summers in Omaha featured an amateur outdoor presentation called The Show Wagon. There I saw another set of distant relatives, but kids all the same, the Kutie brothers, playing Hawaiian Guitars. So Palsy and the Kuties got me thinking about writing songs myself.

And at age 7 or 8, I wrote one - The Mountain Slide. Listening to it now, I realize it is a kind of country fiddle tune, with a dash of South Omaha Polka. Here is a sample:

This leads me to an insight about my young self. From the beginning, I regarded almost all my activities as work — my work: play-acting, writing, singing, song-writing, reading. I took it on with gusto. To say I was serious about it is accurate but misleading. I had learned there was technique involved, and I studied to create a comic effect. In addition, I lived for any chance to manifest grand emotions.

This is an account of my jobs, and the preceding paragraph is about my work. Most of the years of my employment, I assumed that the two were in conflict, my jobs took me away from my work. At the very end of my work life, I realized I had been mistaken. In what way? Read on.

Next installment: Precedents, Part 3 of 3. Robert Murphy emigrated from Ulster as a teen, and wound up the pastor of a South Omaha Church where my family attended. Next we will witness the impact of this impressive scholar/presenter. Then came the proto-employment of childhood, when I got paid as a laborer, paper boy and musician.

Excellent!!